-

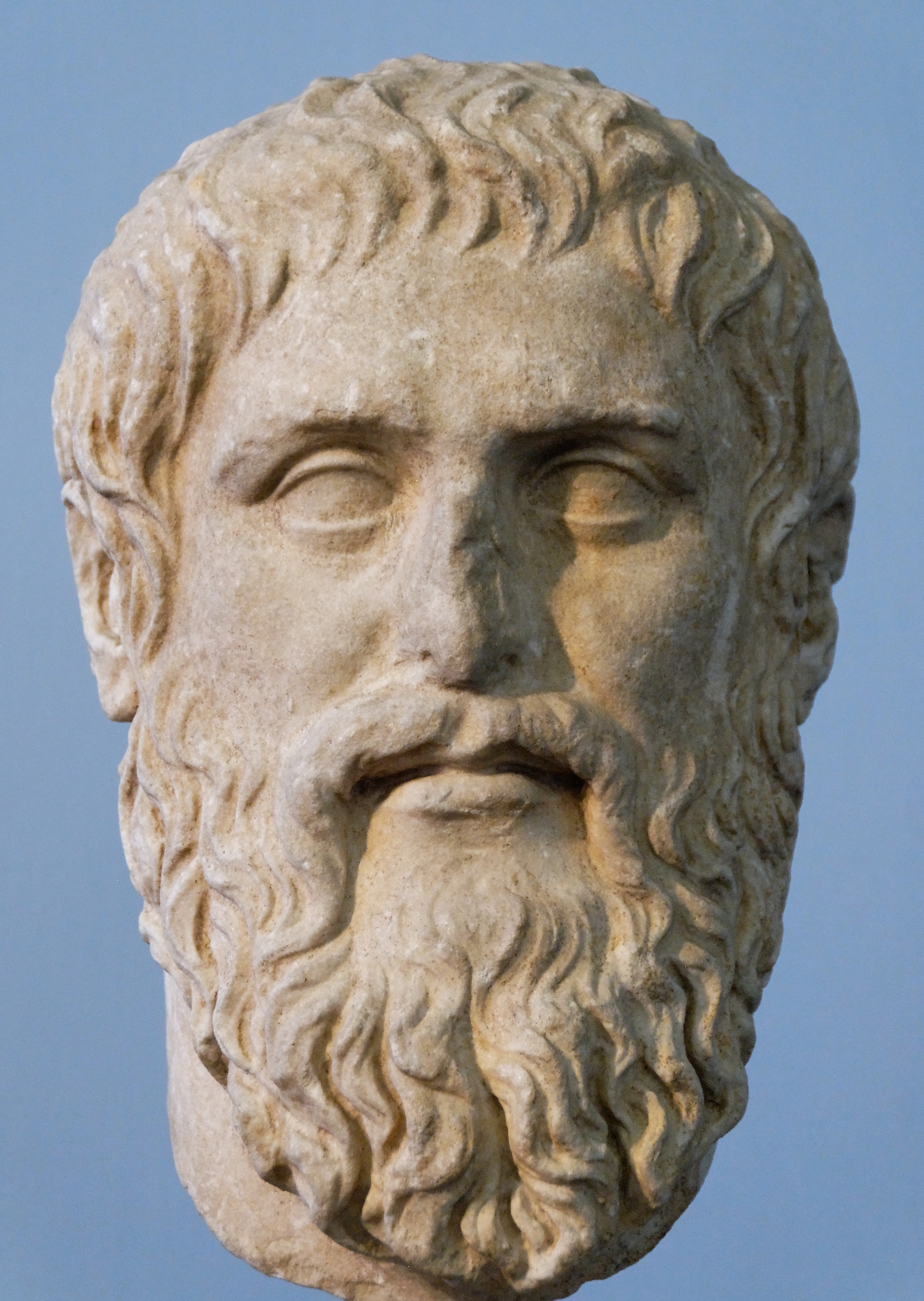

Symposium

09 May 2025 -

Tosti

29 April 2025 -

The Golden Age of Castrati

20 April 2025 -

Zarzuela

17 April 2025

The Art of War

The Art of War is one of the most influential texts on strategy ever written, transcending time, culture, and discipline. Attributed to the Chinese military strategist Sun Tzu (also spelled Sunzi), this ancient treatise on warfare has guided generals, emperors, politicians, and business leaders for over two millennia. Its relevance today—beyond the battlefield—continues to captivate readers with its timeless wisdom on leadership, conflict resolution, and the calculated use of power.

Despite his legendary status, little is definitively known about Sun Tzu. Traditionally, he is said to have lived during the late Spring and Autumn period (approximately 544–496 BCE) in ancient China, a time marked by constant conflict among rival states. According to historical sources such as the Records of the Grand Historian (Shiji) by Sima Qian, Sun Tzu served as a general and strategist under King Helü of the state of Wu. His military acumen reportedly led to several key victories, elevating Wu's power during a volatile period in Chinese history.

Some modern scholars debate whether Sun Tzu was a single historical figure or a composite identity representing a school of thought. Regardless of his precise identity, the text attributed to him has survived as a foundational work of Chinese military philosophy.

The Art of War was not written as a memoir or a historical record of military campaigns, but rather as a strategic manual—concise, aphoristic, and deeply philosophical. It reflects the intellectual environment of its time, where Confucian, Daoist, and Legalist ideas were vying for influence in both civil and military affairs.

The work was designed as a practical guide for commanders, emphasizing the value of intelligence, deception, adaptability, and psychological insight. Sun Tzu posited that true excellence in warfare lies not in fighting, but in achieving victory without combat—a radical departure from more brute-force approaches to war. “The supreme art of war,” he famously states, “is to subdue the enemy without fighting.”

The Art of War is organized into 13 chapters (sometimes referred to as sections or books), each focusing on a specific aspect of warfare. These include topics such as planning, strategy, terrain, espionage, and the use of energy or momentum. Despite its brevity—the text is only about 6,000 Chinese characters—it is remarkably dense with insight.

The writing style is terse, elegant, and highly metaphorical. Rather than lengthy arguments or narratives, Sun Tzu employs short, impactful statements that leave room for interpretation. This style not only made the text easier to memorize, but also lent itself to diverse applications across different times and contexts.

Many passages are expressed in paradoxes or apparent contradictions, such as, “In the midst of chaos, there is also opportunity,” or, “Appear weak when you are strong, and strong when you are weak.” These aphorisms invite the reader to think beyond the obvious and embrace flexibility as the highest form of strength.

The first known translation of The Art of War into a Western language was produced by the French Jesuit missionary Jean Joseph Marie Amiot in 1772. Amiot’s translation, based on a Manchu version of the text, introduced European readers to Chinese military thought for the first time. While pioneering, it was more interpretative than literal and lacked some of the nuance of the original.

In the early 20th century, British sinologist Lionel Giles published a more rigorous and scholarly English translation in 1910. Giles’ work remains one of the most cited and respected versions, notable for its clarity, extensive footnotes, and inclusion of traditional Chinese commentaries. He drew from multiple ancient sources, enhancing the depth and historical accuracy of the translation.

Another notable English version came from Everard Calthrop, who published his own translation in 1905 (slightly earlier than Giles). Though less well-known today, Calthrop’s version aimed for a simpler and more direct rendering of the text, making it accessible to a broader readership at the time.

Since then, The Art of War has been translated and reinterpreted by countless others, each bringing new perspectives or emphasizing different aspects of the work. Notable modern translations include those by Thomas Cleary, who highlighted the text’s Daoist elements; Samuel B. Griffith, who provided a military historian’s lens; and Roger T. Ames, who explored its philosophical depth.

Today, The Art of War is required reading not just in military academies, but also in business schools, leadership seminars, and even sports strategy sessions. Its appeal lies in its universality: the principles of flexibility, preparation, and psychological insight are as applicable in boardrooms as they are on battlefields.

Ultimately, Sun Tzu’s masterwork continues to resonate because it speaks to the fundamental nature of conflict—whether internal or external—and teaches us to face it with clarity, patience, and cunning.

Another 3 years before the Lionel Giles translation is out of copyright, but that doesn't seem to have stopped LibriVox:

0 comments