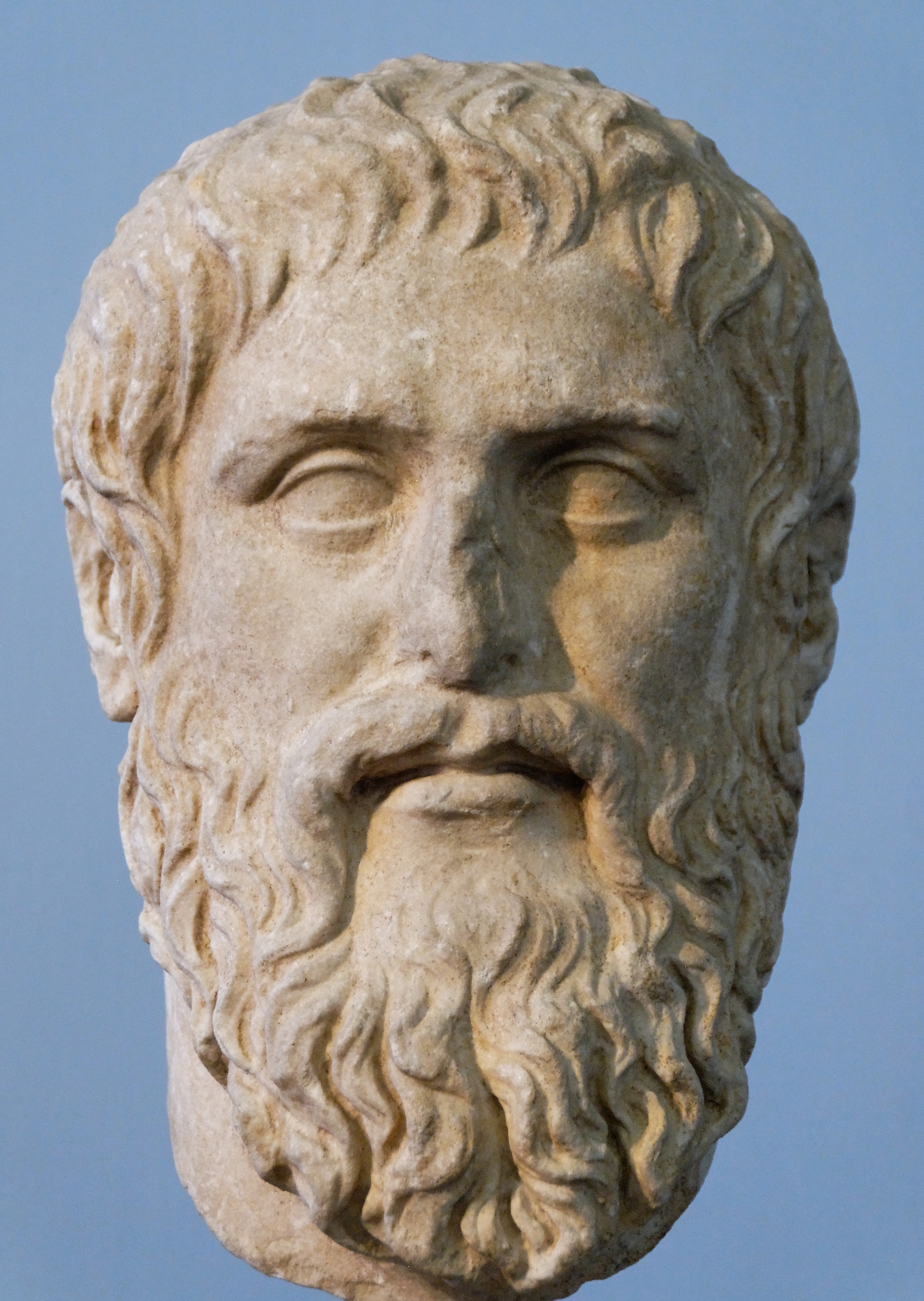

Plato’s Symposium is one of the most influential philosophical texts in the Western canon, composed around 385–370 BCE. Set in the form of a dialogue, the text dramatizes a banquet attended by a group of Athenian intellectuals and artists who take turns giving speeches in praise of Eros, the Greek god of love and desire. While often poetic and humorous, the dialogue explores profound philosophical questions about the nature, purpose, and stages of love.

The Symposium is framed by Apollodorus’ narration of a past event: a drinking party held at the house of the tragedian Agathon. Among the notable speakers are Phaedrus, Pausanias, Eryximachus, Aristophanes, Agathon, Socrates, and—briefly—Alcibiades. Each offers a unique perspective, but the dialogue builds toward the climactic speech by Socrates, which recounts his conversation with Diotima, a wise priestess or philosopher who teaches him the metaphysical dimensions of love.

Diotima introduces the concept that love is not merely desire for physical beauty or sexual gratification but a spiritual aspiration toward truth, wisdom, and immortality. This culminates in her teaching of the Ladder of Love, a progressive ascent from physical attraction to philosophical enlightenment.

The Ladder of Love (also known as the "ascent to the Beautiful") is a metaphorical journey that the lover undertakes, moving from lower to higher forms of love. It represents a process of spiritual and intellectual refinement, where the soul gradually detaches from the particular and ascends toward the universal.

Diotima outlines this ascent as follows:

Love of a Single Beautiful Body: The journey begins with the attraction to one individual’s physical beauty. This is the most immediate and instinctive form of love.

Love of All Beautiful Bodies: Recognizing that beauty in one body is common to others, the lover shifts their focus from the particular to the general.

Love of Beautiful Souls: The lover then comes to value moral and intellectual beauty more than physical appearance, turning attention to virtuous minds and characters.

Love of Beautiful Practices and Laws: The next stage is an appreciation for social order, justice, and institutions that cultivate virtue and beauty in society.

Love of Knowledge: The lover seeks understanding and wisdom, attracted to the beauty found in philosophical truths.

Love of the Form of Beauty Itself: Ultimately, the lover contemplates the eternal, unchanging Form of Beauty—an abstract, perfect ideal that transcends all physical and temporal manifestations.

This final vision, described as a kind of divine revelation, leads to the creation of true virtue and a form of immortality through philosophical insight or the birth of ideas that endure beyond one’s life.

In essence, Plato’s ladder is not just about personal growth but a cosmic vision of love as a force that connects the material world to the divine realm of Forms.

While Plato’s Symposium offers a metaphysical and philosophical model of love's ascent, the Kama Sutra, composed by Vatsyayana in ancient India (circa 3rd–5th century CE), provides a more integrated vision of human pleasure (kāma) as one of life’s core aims (puruṣārthas), alongside dharma (righteousness), artha (material success), and moksha (liberation). The Kama Sutra is often mischaracterized as merely a manual of erotic techniques; in reality, it contains rich philosophical reflections on love, aesthetics, and the social art of living.

In particular, one of its deeper layers—the cultivation of kāma through refined appreciation of beauty, music, conversation, and affection—mirrors early steps on Plato’s Ladder. Both traditions suggest that love begins with sensual attraction but has the potential to be refined and elevated. However, the Kama Sutra emphasizes a balanced life rather than spiritual transcendence. Its ultimate goal is not detachment from desire, but the intelligent enjoyment of it within ethical and social bounds.

Whereas Plato aims at a mystical union with the eternal Form of Beauty, the Kama Sutra aligns love with harmony in human relationships, aesthetic enjoyment, and worldly fulfilment. It’s a horizontal rather than vertical model of love’s perfection.

....

Francesco Paolo Tosti (1846–1916) was a celebrated Italian composer, particularly renowned for his contribution to the genre of the salon and art song, known in Italy as romanze da salotto. His lyrical and sentimental melodies made him one of the most popular vocal composers of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Tosti was born in Ortona, a small coastal town in the Abruzzo region of Italy, on April 9, 1846. He demonstrated musical talent at an early age and was admitted to the Royal College of San Pietro a Majella in Naples, where he studied violin and composition under Saverio Mercadante, one of Italy's leading opera composers. However, poor health and financial hardship forced him to leave the conservatory before completing his studies.

After returning to his hometown, Tosti gradually regained his strength and began teaching and composing. His early songs gained popularity for their melodic charm and emotional appeal, which reflected the romantic sensibilities of the era. He eventually moved to Rome, where his fortunes changed when he was taken under the patronage of Princess Margherita of Savoy, the future Queen of Italy. She appointed him her singing teacher, a prestigious post that gave him access to elite circles in Italian and European society.

In 1875, Tosti moved to London, where he would spend much of his career. His reputation flourished in Britain, and he quickly became a central figure in London's musical life. He was appointed singing master to the Royal Family and counted Queen Victoria, Edward VII, and other royals among his admirers. In 1885, he became a professor of singing at the Royal Academy of Music, and in 1906 he was knighted by King Edward VII—an exceptional honor for a foreign-born artist.

Tosti's compositions were enormously successful during his lifetime. His music, often set to texts by leading Italian poets, was known for its elegance, simplicity, and emotional immediacy. He excelled in writing romanze, short lyrical pieces usually composed for voice and piano, which combined Italian operatic expressiveness with the intimacy of the drawing room. Among his most famous songs are “L’alba separa dalla luce l’ombra,” “La serenata,” “Marechiare,” and “Ideale.”

Tosti's melodic gift, refined harmonic language, and sensitivity to the voice earned him international acclaim. Although critics occasionally dismissed his work as overly sentimental or lightweight, his songs remained beloved by singers and audiences alike for their beauty and emotional depth.

He returned to Italy in his later years and died in Rome on December 2, 1916. Today, Francesco Paolo Tosti is remembered as one of the great masters of the art song and a key figure in the cultural exchange between Italy and the English-speaking world during the Belle Époque.

Sogno (Italian for "Dream") is one of Francesco Paolo Tosti’s most cherished art songs, composed around 1891. The text was written by Riccardo Mazzola, and the song exemplifies Tosti’s gift for crafting tender, melancholic melodies that resonate deeply with both performer and listener.

The song’s narrative centers on the haunting memory of a dream in which the speaker experiences a moment of joy and love—only to awaken to solitude and heartbreak. The melody unfolds with lyrical grace, supported by a delicate and expressive piano accompaniment. Like many of Tosti’s songs, Sogno is direct in its emotional appeal, blending poetic nostalgia with a refined musical language.

Tosti’s characteristic style—elegant yet passionate—is fully present in Sogno, making it a favorite among lyric tenors and sopranos. It allows the singer to explore a wide emotional palette, from wistful longing to quiet despair. The piece remains a staple in the Italian song repertoire and continues to be performed in recitals and competitions, cherished for its melodic purity and expressive power.

Image is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.....

In the 17th and 18th centuries they were the stars of the opera scene — it was the golden age of the castrati. (Talk Classical) These ethereal male singers, capable of soaring above the orchestra with astonishing vocal power and agility, dominated Europe's grandest opera houses and cathedrals. Their voices — neither fully male nor female — were the result of a drastic and controversial practice: prepubescent castration.

Castrati were not born stars — they were chosen. Selection often took place at a young age, typically between seven and nine, when a boy showed early vocal promise. Some saw it as an honour for which they were fully ready to endure the pain. In other cases, families, often impoverished, saw the potential for social elevation and financial reward. Some were persuaded, others coerced. In rare instances, boys were castrated without full parental consent or under false medical pretences (such as curing a hernia).

Before undergoing the operation, boys would typically already be enrolled in rigorous musical education, often in church-run institutions called conservatori in Italy. These were not merely schools but all-encompassing musical boot camps, where students were expected to master vocal technique, musicianship, and sometimes multiple instruments.

The castration procedure itself was shrouded in secrecy, as it was technically illegal in many regions. The exact methods varied, but a few consistent details emerge from historical accounts, ranging from cutting through the scrotum and the sperm duct to complete severance or crushing of organs. The boy might be submerged in a hot bath to relax the body and reduce blood flow, and a strong dose of alcohol was administered to dull the pain. There was no real anaesthetic.

Mortality rates from the procedure are unknown but undoubtedly real. Infection was a major risk, and without modern sterilization or antibiotics, some boys did not survive. Those who did were altered life long — physically, hormonally, and socially.

Once recovered, the boys resumed their musical training with renewed intensity. The castration prevented their voices from deepening, preserving the high, angelic timbre of childhood. However, as they matured, their lungs and ribcages grew to adult male proportions — often larger due to hormonal imbalances — giving them tremendous breath control and vocal power. This combination produced the unique castrato sound: a fusion of strength and purity, agility and resonance.

Many became superstars, idolized across Europe. Others faded into obscurity. The most successful could command enormous fees, live lavish lifestyles, and receive the adulation of the masses. Farinelli, one of the most famous castrati, was so revered that he was later brought to the Spanish court to sing nightly for a depressed king.

Castrati occupied a strange place in society. Physically and hormonally altered, their bodies often grew disproportionately — some were unnaturally tall with elongated limbs, leading to what we now recognize as forms of eunuchoid gigantism. They were not generally homosexual, despite modern assumptions. Many had romantic or sexual relationships with women, but these relationships were inherently complicated. One successful castrato, thwarted in love by his physical disposition, threw his empty purse at his father, signifying that his wealth did not make up for the procedure his father had sent him for. The Catholic Church, which often employed castrati in its choirs, prohibited them from marrying on the grounds of their infertility. A deep hypocrisy ran through the Church’s stance — while officially denouncing the practice, it simultaneously depended on castrati to fill its choirs, particularly the Sistine Chapel, where women were forbidden from singing.

Castrati were also known to flaunt fashion and wealth. In some cities, they could be seen strutting through town in full performance regalia, indulging in shopping sprees and attracting throngs of admirers — both male and female. Their ambiguous status made them a kind of early celebrity: alluring, strange, and socially transgressive.

What made the castrato voice so extraordinary — and so obsessively sought after — was its uncanny blend of purity and power. Unlike adult male singers whose voices dropped in adolescence, castrati retained the high, clear vocal range of a prepubescent boy. This gave them a brightness and clarity often associated with the female voice, but with key differences. Castrati had far greater lung capacity, physical stamina, and muscular control than women — their elongated ribs and unbroken vocal folds allowed them to produce long, sustained phrases with incredible volume and precision. Female singers could certainly sing high, but they lacked the sheer vocal heft of a full-grown male chest supporting those same pitches. In a way, the castrato voice was considered "more perfect" than the female voice: it had the sweetness of a soprano, but could cut through orchestras in large halls, something female singers often struggled with in an era before microphones. This fusion of innocence and grandeur made their voices seem almost otherworldly — and perhaps explains why audiences, composers, and patrons alike were willing to overlook the brutal means by which such voices were created.

Before microphones and electronic amplification, opera relied entirely on the natural power of the human voice to fill vast theatres. Composers like Handel, Gluck, Mozart, Vivaldi, wrote arias specifically for castrati, knowing their unparalleled range and endurance. Castrati could out-sing their peers, holding notes longer, leaping octaves with ease, and delivering performances that bordered on the supernatural.

However, by the 19th century, the practice began to decline. Enlightenment thinking, changing tastes, and increasing medical scrutiny led to public discomfort with the tradition. The last known castrato, Alessandro Moreschi, died in 1922 — a relic of a bygone age. His voice was even recorded, giving us a haunting glimpse into a world that is, thankfully, no longer physically sustained, but whose music still resonates.

An aria written by Vivaldi for the castrato role of Zelim in his opera "La verità in cimanto":

....

Zarzuela is a fascinating and richly textured genre of musical theatre that holds a significant place in Spanish culture. It blends elements of both opera and operetta, but with distinctive features that set it apart from the more widely recognized traditions of Italian opera or German operetta.

Zarzuela has its roots in 17th-century Spain, though the genre that we recognize today began to take shape in the 19th century. The word zarzuela comes from the Spanish term for a type of royal hunting lodge—La Zarzuela—where performances combining music, dialogue, and dance were staged for the Spanish court in the early 1600s. However, it wasn’t until the late 19th century that the genre fully developed into the form we know today, marked by a mixture of spoken dialogue, singing, and sometimes dance, reflecting both the operatic and operetta traditions.

The genre originally evolved in Spain as a response to the popularity of Italian opera. Initially, it was a lighter, less formal style, often depicting popular themes and the daily lives of ordinary people, as opposed to the grandiose narratives of Italian opera. Its combination of serious and comic elements made zarzuela an appealing middle ground between high art and more accessible entertainment.

Zarzuela flourished in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, especially during Spain's "Golden Age" of zarzuela in the 1860s to the 1930s. The genre evolved in various directions:

Early zarzuela was quite simple in its musical style, incorporating folk music and popular tunes, often with a satirical or comic bent.

By the 20th century, composers like Francisco Álvarez García, Ruperto Chapí, José Serrano, and Manuel de Falla contributed significantly to zarzuela's development, incorporating more sophisticated orchestration and harmonies. Zarzuela reached its peak with composers like Tomás Bretón and Francisco José Álvarez who created works that would be performed well into the 20th century.

The genre became particularly popular in Madrid and in the broader Spanish-speaking world, with many zarzuela companies performing across Spain and Latin America.

Zarzuela blends spoken dialogue and sung music, often in alternating sections or in a more integrated format than the operatic arias and recitatives. The music itself is usually quite diverse, moving between arias, duets, choruses, and dances, often reflecting a variety of moods, from lighthearted and comic to deeply serious or even tragic.

"Zarzuela Grande" (Grand Zarzuela): Larger, more elaborate works with full orchestral scores, often containing multiple acts, elaborate staging, and more dramatic themes.

"Zarzuela Chica" (Light Zarzuela): Shorter and lighter in tone, focusing more on simple storylines and melodies. It was more accessible to a wider audience.

Another important feature is the frequent use of flamenco and castanets, adding a distinctive Spanish flavor to the musical score.

Zarzuela shares many similarities with operetta, particularly the lighter, comedic, and more accessible aspects of the genre. Both operetta and zarzuela use a similar form with spoken dialogue and music, though there are some notable differences:

Zarzuela is inherently Spanish, with lyrics and music heavily influenced by Spanish folk traditions, flamenco, and regional styles. In contrast, operettas, particularly those in German, English, and French traditions, often have different cultural and linguistic roots.

While operettas often feature a more European-style operatic music, zarzuela incorporates distinctly Spanish rhythms and melodies. Flamenco, jota, fandango, and other folk dances often appear in zarzuela, while operetta tends to favour waltzes, polkas, and other European dance forms.

Zarzuela often has a more direct connection to Spanish drama and literature, dealing with local stories, humour, and regional dialects. Operettas, particularly those by composers like Johann Strauss II (Viennese operetta) or Gilbert and Sullivan (British), often satirize society and politics, though the humour is more universal.

While zarzuela once held a prominent place in Spanish cultural life, particularly in the 19th and early 20th centuries, its status in the broader classical repertoire today is more niche. In Spain, however, zarzuela remains an integral part of the national musical heritage, with annual festivals and performances still attracting large audiences.

Outside of Spain, zarzuela’s presence is somewhat limited but still appreciated in niche circles. In recent years, there has been a resurgence of interest in zarzuela, particularly in Latin American countries, and occasionally in major opera houses outside of Spain.

Famous zarzuela works like "La verbena de la Paloma" by Tomás Bretón, "Doña Francisquita" by Amadeo Vives, and "El barberillo de Lavapiés" by Francisco José Álvarez remain in the repertoires of Spanish opera companies. Outside of Spain, however, they are much rarer in performance, though there is an occasional revival.

Zarzuela is a unique and beloved part of the Spanish musical and theatrical tradition, blending elements of opera, operetta, and musical theatre with a distinctly Spanish flavour. While it shares similarities with operetta, particularly in its mixture of music and dialogue, zarzuela is set apart by its local influences and its ability to reflect the culture, customs, and humor of Spain. Although its popularity outside Spain has been somewhat limited, it remains a vital part of the Spanish cultural identity and continues to find new audiences, particularly in the 21st century.

Photo/image by Luis García (Zaqarbal) ⓒ Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License....

The Kama Sutra is often popularly reduced to its erotic chapters, but such a narrow view does little justice to its full philosophical scope and cultural significance. In reality, this ancient Indian text is a complex and nuanced treatise on human life, offering insights into ethics, aesthetics, relationships, social norms, and personal conduct. At its heart, it is a sophisticated exploration of how to live well and harmoniously within the bounds of dharma (duty), artha (prosperity), and kama (pleasure or desire)—three of the four classical goals of Hindu philosophy, the fourth being moksha (liberation).

Traditionally attributed to a sage named Vatsyayana, the Kama Sutra was likely composed in the 3rd century CE, though Vatsyayana himself refers to earlier sources, indicating that his work is more a compilation and synthesis than an entirely original creation. He presents his text not as a book of personal invention, but as a considered distillation of centuries of earlier wisdom and discourse.

According to the tradition Vatsyayana cites, the origins of the Kama Sutra can be traced back to a divine source. The primordial being Prajapati, the creator deity in Vedic cosmology, is said to have composed a vast body of knowledge—some 100,000 verses—addressing every aspect of life. From this immense collection, the god Nandi, who is also closely associated with Shiva, extracted and organized the teachings specifically related to kama, the pursuit of aesthetic and sensual pleasure. This subset of verses formed the basis of a genre known as the Kama Shastra, or the science of desire.

Over time, scholars and sages successively refined and abridged this material. These efforts culminated in the work of Vatsyayana, who compiled what remained into a cohesive treatise of seven books, each divided into chapters addressing various themes of love, domestic life, and social etiquette. His Kama Sutra—“sutra” meaning aphorism or thread—was intended as a practical and ethical guide to the art of living in accordance with human nature.

It is essential to recognize that the Kama Sutra is not a manual of sexual technique, as it is often portrayed in modern media. While it does address the physical aspects of intimacy, these form only a small part of a much broader vision. The text concerns itself with topics such as courtship, the duties of husbands and wives, the dynamics of attraction, the psychology of desire, and even social customs like matchmaking, household management, and the cultivation of personal charm and refinement.

In this sense, the Kama Sutra is closely aligned with two other important texts drawn from the original 100,000 verses. The Dharma Shastra deals with righteous conduct, laws, and duties—the ethical and moral framework of society. The Artha Shastra, attributed to the strategist Kautilya (also known as Chanakya), addresses governance, economics, and the pursuit of material success. Together with the Kama Sutra, these works reflect the ancient Indian conception of a well-rounded life: one in which duty, wealth, and pleasure are pursued in balance, each supporting the others.

Vatsyayana himself makes it clear that kama should never be pursued in contradiction to dharma or artha. In his view, pleasure is not inherently sinful or frivolous, but rather a natural and essential part of human life. When sought with sensitivity, intelligence, and in the right context, it becomes a source of joy and personal growth. He also emphasizes that the Kama Sutra is not meant to be followed blindly; it should be adapted to time, place, and individual temperament.

The historical impact of the Kama Sutra has been wide-ranging. Though it fell into relative obscurity during certain periods, especially under more conservative religious or colonial influences, it has experienced revivals and reinterpretations over the centuries. Its first major English translation, published in the 19th century by Sir Richard Burton and Indian scholar Bhagirath Shastri (under the guidance of Pandit Shivaram Parashuram Bhide), helped reintroduce the text to the world, though not without contributing to its eroticized reputation in the West.

Today, scholars increasingly recognize the Kama Sutra as a serious and sophisticated document of cultural history. It provides a rare window into the social life of ancient India, offering evidence of a society that was in many ways more frank, curious, and pluralistic than the assumptions we may carry about antiquity.

Ultimately, to understand the Kama Sutra is to appreciate its broader message: that a fulfilling life requires harmony between duty, prosperity, and pleasure. Vatsyayana’s work invites us to consider not just how we seek pleasure, but why—and how that pursuit can be part of a meaningful, ethical, and joyful life.

Maybe this video provides insight into the way Kama Sutra has fit into Indian life. It has been freely available on numerous age-restricted and non-restricted video sites for well over a decade now. Here, local copy and YouTube link.

Kama Sutra - A Tale of Love (1996)

....

Anja Harteros, born on July 23, 1972, in Bergneustadt, North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany, is a distinguished soprano renowned for her interpretations of both lyric and dramatic roles in the operatic repertoire. Of Greek and German descent, she was encouraged from a young age to pursue classical music and singing. Her talent was nurtured during her studies at the Hochschule für Musik Köln under the guidance of Liselotte Hammes.

Harteros's professional career commenced in the mid-1990s with ensemble positions at theaters in Gelsenkirchen, Wuppertal, and Bonn. A pivotal moment came in 1999 when she won the Cardiff Singer of the World competition, becoming the first German to achieve this honor. This victory led to an invitation from Sir Peter Jonas to perform the role of Agathe in "Der Freischütz" at the Bavarian State Opera, marking the beginning of a significant association with the company.

Throughout her illustrious career, Harteros has graced many of the world's leading opera houses. At the Metropolitan Opera in New York, she debuted as Countess Almaviva in "Le nozze di Figaro" in 2003, later portraying Violetta in "La traviata" and Donna Anna in "Don Giovanni" under the baton of James Levine. Her performances at the Paris Opéra have included roles such as Eva in "Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg," Fiordiligi in "Così fan tutte," and Leonora in "La forza del destino." At London's Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, she has been acclaimed for her portrayal of Desdemona in "Otello." La Scala in Milan has featured her as Alcina in Handel's opera, Elsa in Wagner's "Lohengrin," and Amelia in Verdi's "Simon Boccanegra" under Daniel Barenboim.

Harteros's repertoire encompasses a wide range of roles, reflecting her versatility and depth as a performer. Notable portrayals include the Countess in "The Marriage of Figaro," Donna Anna in "Don Giovanni," Violetta in "La traviata," Desdemona in "Otello," Arabella in Strauss's "Arabella," and the Marschallin in "Der Rosenkavalier." Her interpretations of Wagnerian heroines such as Elsa in "Lohengrin" and Elisabeth in "Tannhäuser" have also garnered critical acclaim.

In recognition of her contributions to opera, Harteros was named Bavarian Kammersängerin in 2007, the youngest recipient of this title at the time. She received the Bavarian Order of Merit in 2018 and has been honored with the Meistersinger Medal. Her artistry continues to captivate audiences worldwide, solidifying her status as one of the preeminent sopranos of her generation.

Doing justice to the sublime orchestrations by Richard Strauss of the verses by Hesse and Eichendorff in his Four Last Songs requires exceptional qualities: maturity of mind and character, with a voice at its peak. This is one of the most outstanding performances since that of Leontyne Price and Jessye Norman.

Photo/image by carolanbg ⓒ Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 2.0 License.

The Art of War is one of the most influential texts on strategy ever written, transcending time, culture, and discipline. Attributed to the Chinese military strategist Sun Tzu (also spelled Sunzi), this ancient treatise on warfare has guided generals, emperors, politicians, and business leaders for over two millennia. Its relevance today—beyond the battlefield—continues to captivate readers with its timeless wisdom on leadership, conflict resolution, and the calculated use of power.

Despite his legendary status, little is definitively known about Sun Tzu. Traditionally, he is said to have lived during the late Spring and Autumn period (approximately 544–496 BCE) in ancient China, a time marked by constant conflict among rival states. According to historical sources such as the Records of the Grand Historian (Shiji) by Sima Qian, Sun Tzu served as a general and strategist under King Helü of the state of Wu. His military acumen reportedly led to several key victories, elevating Wu's power during a volatile period in Chinese history.

Some modern scholars debate whether Sun Tzu was a single historical figure or a composite identity representing a school of thought. Regardless of his precise identity, the text attributed to him has survived as a foundational work of Chinese military philosophy.

The Art of War was not written as a memoir or a historical record of military campaigns, but rather as a strategic manual—concise, aphoristic, and deeply philosophical. It reflects the intellectual environment of its time, where Confucian, Daoist, and Legalist ideas were vying for influence in both civil and military affairs.

The work was designed as a practical guide for commanders, emphasizing the value of intelligence, deception, adaptability, and psychological insight. Sun Tzu posited that true excellence in warfare lies not in fighting, but in achieving victory without combat—a radical departure from more brute-force approaches to war. “The supreme art of war,” he famously states, “is to subdue the enemy without fighting.”

The Art of War is organized into 13 chapters (sometimes referred to as sections or books), each focusing on a specific aspect of warfare. These include topics such as planning, strategy, terrain, espionage, and the use of energy or momentum. Despite its brevity—the text is only about 6,000 Chinese characters—it is remarkably dense with insight.

The writing style is terse, elegant, and highly metaphorical. Rather than lengthy arguments or narratives, Sun Tzu employs short, impactful statements that leave room for interpretation. This style not only made the text easier to memorize, but also lent itself to diverse applications across different times and contexts.

Many passages are expressed in paradoxes or apparent contradictions, such as, “In the midst of chaos, there is also opportunity,” or, “Appear weak when you are strong, and strong when you are weak.” These aphorisms invite the reader to think beyond the obvious and embrace flexibility as the highest form of strength.

The first known translation of The Art of War into a Western language was produced by the French Jesuit missionary Jean Joseph Marie Amiot in 1772. Amiot’s translation, based on a Manchu version of the text, introduced European readers to Chinese military thought for the first time. While pioneering, it was more interpretative than literal and lacked some of the nuance of the original.

In the early 20th century, British sinologist Lionel Giles published a more rigorous and scholarly English translation in 1910. Giles’ work remains one of the most cited and respected versions, notable for its clarity, extensive footnotes, and inclusion of traditional Chinese commentaries. He drew from multiple ancient sources, enhancing the depth and historical accuracy of the translation.

Another notable English version came from Everard Calthrop, who published his own translation in 1905 (slightly earlier than Giles). Though less well-known today, Calthrop’s version aimed for a simpler and more direct rendering of the text, making it accessible to a broader readership at the time.

Since then, The Art of War has been translated and reinterpreted by countless others, each bringing new perspectives or emphasizing different aspects of the work. Notable modern translations include those by Thomas Cleary, who highlighted the text’s Daoist elements; Samuel B. Griffith, who provided a military historian’s lens; and Roger T. Ames, who explored its philosophical depth.

Today, The Art of War is required reading not just in military academies, but also in business schools, leadership seminars, and even sports strategy sessions. Its appeal lies in its universality: the principles of flexibility, preparation, and psychological insight are as applicable in boardrooms as they are on battlefields.

Ultimately, Sun Tzu’s masterwork continues to resonate because it speaks to the fundamental nature of conflict—whether internal or external—and teaches us to face it with clarity, patience, and cunning.

Another 3 years before the Lionel Giles translation is out of copyright, but that doesn't seem to have stopped LibriVox:

....

The book by D Albrecht Thoma is no stuffy religious book even if it's about the woman who became the wife of the Reformer Martin Luther.

An historical picture of her life, or historical life picture, it describes a vivid picture of the life of this woman, and those surrounding her. Her entry into a convent, her escape in a fish barrel, her marriage to Martin Luther, their acquisition of farmland, visitors to their home, their (non-stuffy) lifestyle, problems with opponents, war, and plague. A woman still close to the hearts of many Germans today.

....

Antonio Vivaldi (1678–1741) was one of the most prolific and influential composers of the Baroque period. Born in Venice on March 4, 1678, he was the son of Giovanni Battista Vivaldi, a professional violinist. His father introduced him to music and likely trained him in the violin, an instrument Antonio would later elevate to new expressive heights.

Though his musical talents were evident from a young age, Vivaldi entered the priesthood and was ordained in 1703. Because of his striking red hair, he earned the nickname Il Prete Rosso—"The Red Priest." However, his clerical career was brief; a chronic illness, generally believed to be asthma, left him unable to deliver mass. This "voice problem" effectively ended his liturgical duties, but it did not deter him from continuing in ecclesiastical service in other ways.

That same year, he was appointed as maestro di violino (violin master) at the Ospedale della Pietà, a Venetian orphanage for girls renowned for its musical education. It was here that Vivaldi composed many of his sacred and instrumental works, training and conducting the institution’s all-female orchestra, which became famous throughout Europe.

Vivaldi's output was staggering—over 750 works, including over 500 concertos, about 50 operas (of which around 20 are extant), numerous sacred choral pieces, and a wealth of chamber music. While his instrumental concertos—particularly The Four Seasons—are his most celebrated today, in his own time, he was equally known for his operas and vocal music, which were frequently performed across Italy and beyond.

During his operatic career, Vivaldi formed a close professional relationship with soprano Anna Girò, who became his favorite singer and frequent leading lady. She and her sister lived with him for a time, sparking rumors of impropriety. Vivaldi maintained that their relationship was strictly platonic and spiritual, but the closeness did raise eyebrows within the Church and society.

These tensions, combined with shifting musical tastes and possible financial difficulties, contributed to Vivaldi’s eventual departure from Venice. In the late 1730s, he moved to Vienna, hoping to find favor at the imperial court of Emperor Charles VI, who admired his work. However, the emperor’s sudden death in 1740 dashed Vivaldi’s hopes for patronage.

Vivaldi died in Vienna on July 28, 1741, in relative obscurity and poverty. He was buried in a simple grave, and his music soon faded from public memory.

The modern renaissance of Vivaldi’s music is a remarkable chapter in music history. Despite his immense output, Vivaldi’s music was largely forgotten for nearly two centuries after his death. His resurgence began in earnest in 1926, when a pivotal discovery was made at the Collegio di San Carlo, near Turin. In an effort to fund repairs, the college planned to sell old manuscripts from its library.

Musicologist Alberto Gentili examined the collection and found it contained numerous handwritten Vivaldi manuscripts. Recognizing their value, he convinced a Turin industrialist to purchase them for the National Library of Turin, in memory of his recently deceased son.

These manuscripts had originally been collected in the 18th century by Count Giacomo Durazzo, but how they came into his possession remains unknown. Intriguingly, catalog numbers on the volumes suggested that some were missing. In 1930, the missing manuscripts were located in another branch of the Durazzo family and were added to the Turin collection.

After World War II, Antonio Fana and Angelo Ephrikian founded the Istituto Italiano Antonio Vivaldi. They partnered with the publisher Ricordi to undertake the monumental task of printing Vivaldi’s complete works—over 750 pieces. This printing project was critical: without available scores, musicians could not perform Vivaldi’s works.

Thanks to these efforts, Vivaldi’s music began to be heard again. Since the 1950s, his popularity has grown exponentially, culminating in a global appreciation that would have seemed unimaginable during the years following his death. Today, his music is celebrated for its brilliance, energy, and emotional depth—a testament to the enduring genius of the Red Priest.....

Ekaterina Bakanova, a distinguished Russian soprano, was born in Orenburg, a city known for its unique natural contrasts on the border of Europe and Asia. She grew up in Mednogorsk, a small town in the Ural Mountains. Her mother hails from Melitopol, Ukraine, while her father has Russian roots. Both had jobs at the Magnitogorsk Iron and Steel Works. As an only child, she bore significant responsibility within her family.

Bakanova's musical journey began at the age of twelve, when she enrolled in a local art school. Due to her late start, she was limited to studying the accordion, as other instruments required earlier enrolment. Encouraged by her grandmother, who believed the accordion would provide opportunities to perform at events and earn income, Ekaterina pursued this path for five years. Her innate musicality was evident, leading her to explore other avenues in music.

She furthered her education at the Gnessin Institute in Moscow, where she studied singing, piano, and accordion. Currently, she continues to refine her vocal skills under the guidance of Gabriella Ravazzi in Genoa, Italy.

Bakanova's professional career is marked by performances at prestigious international opera houses under renowned conductors. She has graced stages such as the Royal Opera House in Covent Garden, Arena di Verona, National Centre for the Performing Arts in Beijing, Teatro La Fenice in Venice, and Teatro Regio di Parma. Her collaborations include working with conductors like Plácido Domingo, Myung-Whun Chung, and Stefano Ranzani. Directors such as Franco Zeffirelli and Robert Carsen have also featured her in their productions.

A pivotal moment in her career occurred in July 2015 when she made a surprise debut as Violetta in "La Traviata" at the Royal Opera House, stepping in on short notice and delivering a performance that garnered widespread acclaim. Her portrayal of Violetta has since become a signature role. That same year, she performed as Donna Anna in Mozart’s "Don Giovanni" at the Arena di Verona, earning the Giulietta Prize for best singer of the 2015 festival. In 2016, she was recognized as one of the best female emerging singers at the International Opera Awards.

In 2020, Bakanova was honoured as an Ambassador of Italian Culture in the World by NewsReminder, in collaboration with the European Parliament Italian Office, acknowledging her contributions to promoting Italian culture globally. The following year, she received the Giuseppe Sciacca International Prize in Italy.

Currently, Ekaterina Bakanova continues to captivate audiences worldwide with her powerful performances and dedication to the operatic art form.

Photo/image by Peter Komposch © licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 2.0 License.....

German, 14/24 February 1621, Greifswald – 31 July/10 August 1638, Greifswald.

A splendid-looking young woman, would do well in our current society, or rather she might do our current society well. She might also bring her dressmaker back with her!

She was a remarkable German poet whose talent and voice emerged during the turbulent era of the Thirty Years' War. Often referred to as the “Pomeranian Sappho,” she began writing poetry at about 10 years old. She was one of the very few women during the Baroque period who dared to go against taboo and publish her texts, and did so as a teenager. People, events, history.

A child prodigy, she grew up as the youngest daughter of a patrician family in Greifswald, her father the mayor of the town. She received an education from a private tutor, which was unusual for a girl in the 17th century, even for one with wealthy parents. But Sibylla's father recognized and encouraged his daughter's talent. She explained in a letter why she wrote poetry: Not to gain a handful of favour or honour, but out of a love of history, a fascination with poetry, and a desire to practise it. She didn't want to let the words she found disappear into a drawer.

In 1634, when she was 13, the pastor and teacher Samuel Gerlach became aware of her. He introduced her to Martin Opitz's verse school, and she became influenced by him. Samuel Gerlach also served as her private tutor. Ultimately, she entered the avant-garde literary scene of the time. At 17, she may have been better than Goethe or Rilke.

She died at that age after having drunk infected water.

This song by Rachmaninov is a very popular piece among sopranos with Russian. The River Irwell as it meanders towards forming the Manchester Ship Canal – if it wasn't for the 'ouses in between! Maybe not sunrise or sunset, but daylight on the great Russian plains.

Piano only version:

Photo: Norfolk Broads 1971, from windmill, probably this one.....

This opera seria by Handel was first performed in 1729 at the King's Theatre in London .

Berengario, an Italian duke, and Matilde, his wife, murder the King of Italy and plot to force his widow, Adelaide, to marry their son, Idelberto, who's maybe something of a kind-hearted sop.

Lotario, the King of Germany, aims to claim the Italian throne.

Adelaide and Lotario fall in love despite her grief over the murder of her husband.

In the machinations, Mathilde has Adelaide thrown in a dungeon.

Lotario, storming the castle, defeats Berengario and imprisons him. Lotario regains Adelaide.

Lotario lets Adelaide decide what to do with Berengario and Matilde. Adelaide shows them forgiveness, and Idelberto becomes King of Italy out of gratitude for saving her life while held by Mathilde and Berengario.

In this excerpt, Adelaide is showing her strength of character while held prisoner my Mathilde:

....

A very favourite Puccini opera, first performed in 1917.It was obscured by the First World War, and not immediately taken to because no one dies and no devastation occurs. Gaining popularity now, the libretto having come into the public domain, making it more accessible to more people. In the current day, it may well appeal particularly to the transgender community, particularly the production with Bakanova.

Magda, a courtesan, is having a get-together, a soirée, with some friends in the house of her keeper, Rambaldo. Ruggero, someone Ranbaldo knows, arrives on a visit to Paris. In order to show him the town, they decide to go to the night venue, Bullier's. The maid, Lisette, who's attached to the poet, Prunier, dresses herself up in her mistresses clothes to go with the party to Bullier's, while Magda decides to go disguised as a maid or grisette. At Bullier's, Magda falls in love with Ruggerro, and they go off for a romantic life in the south of France. However, Magda, a courtesan, cannot "hope to enter the family home" of Ruggero, they cannot marry, and she must go back to her past life.

Puccini revised the ending of the opera at least twice.

Magda: Sicilia

Magda: Bakanona

Magda: Gheorghiu

Magda: Arteta

....

Vivaldi's 13th opera, first performed durimg the Venice Carnival of 1720

A truly outstanding Baroque opera with beautiful music and unforgettable, wide-ranging arias.

The sultana (Rustena) and the sultan's favourite concubine (Damira) have had babies at the same time. The sultan (Mamud) ordered Damira to swap the babies so that she brings up the heir to the throne, Zelim, while Rustina, unknowingly, brings up Damira's son, Melindo, to expect to inherit the throne. The sultan now wants to let the whole thing out ...

....